I recently had the opportunity to chat with Dr. James McGrath, senior lecturer at Leeds Beckett University and author of Naming Adult Autism: Culture, Science, Identity. James was kind enough to grant me an interview about his fabulous book.

Buy Naming Adult Autism here on Amazon.

Find James on Twitter:@DrJamesMcGrath

SARA: Hello, James! Thank you for agreeing to do this interview about your book. For those readers who don’t know you, can you please tell us a little about yourself?

JAMES: I’m a senior lecturer in Literature and the Humanities at Leeds Beckett University. I was diagnosed autistic in my thirties. In some ways it was a shock, as well as a relief – but I’d always known there was something ‘different’ about most other people. They didn’t seem to need time being silent or being alone each day in the way I did, and their particular interests – sport, television and dating – usually seemed quite odd to me.

My first book has recently been published, and it’s called Naming Adult Autism: Culture, Science, Identity. It’s an academic study, but is also openly autobiographical at different intervals. As well as the scholarly side of things, I write poems. On and off, I’ve been getting poems published in journals since I was 19. One of the book’s chapters, called ‘Title’, is a three-line poem. The other four chapters are about 20,000 words each but divided into themed parts.

As well as looking at novels, poetry, films and songs involving autism, the book experiments with literary critical approaches to the science of autism, which I’ll say more about later.

SARA: It’s easy to see that Naming Adult Autism: Culture, Science, Identity is a truly throughly-researched and work-intensive labor of love. How long did it take to write from envisioning to publishing?

JAMES: It took me three years and three months from signing the publisher’s contract to delivering the manuscript. But many of these thoughts had been with me since childhood, before I knew the word ‘autism’. It’s not my first publication on the subject, but it is my first book. And Naming Adult Autism is the first time I’ve written ‘publicly’ about autism and my own life.

I love your expression ‘work-intensive labor of love’, by the way! It was certainly very intense. Writing the book became absolutely everything to me. So on good writing days, everything felt great – and on bad days, if I couldn’t properly focus, everything felt terrible.

When I held the first copies of the published book in my hand, I felt good but strange. The greatest highs in the whole experience – in my entire life, even – came in the writing process itself, and in the feeling of just breathing in at the end of a good day with the writing.

SARA: What was that process like for you and how did you handle any executive dysfunction challenges?

JAMES: Executive functioning – being able to do the things I need to (from major work tasks down to seemingly trivial things like shopping) has always depended on me having a kind of routine. Many autistic people frequently struggle with executive functioning. But if I can settle into a routine, these things become much easier. The problems come for me when routine gets thrown.

The writing took a year to get going, which scared me. The delay was largely because of my struggle with some large, unexpected circumstances. Two days after I signed the book contract, my then-landlord announced I had to leave the attic flat that had been my home within two months, so he could sell it. I was utterly lost, and it’s a painful time to remember. The practicalities of finding a new place to rent, of waiting to find out if I had got the place I wanted, and of packing the chaos of my life into box after box, were catatonically stressful. The most heartbreaking thing was having to say goodbye to a lovely cat called Mousey who lived in the house.

The sheer – I mean sheer like a cliff – personal, practical and emotional upheaval for an autistic adult being forced to leave their home can be unspeakably distressing. And that was very much the situation for me. It took over a year for the disorientation to settle, because the aftermath of the move was almost equally difficult.

The problem I had was that having moved quite abruptly to a new living space, I just wasn’t settling in to any kind of routine. The light in the room felt wrong, and therefore everything felt wrong. I’d attempt new routines but they just weren’t working. My heart just wasn’t in them.

What I needed was a pattern, a template experience of a day – or even just of, say, a Friday or a Wednesday – which I could enjoy once and then repeat and vary as felt right. But I somehow couldn’t get that to happen. Not having a routine meant having nothing clear to look forward to. But amidst all that chaos, a quietly life-changing realisation occurred for me.

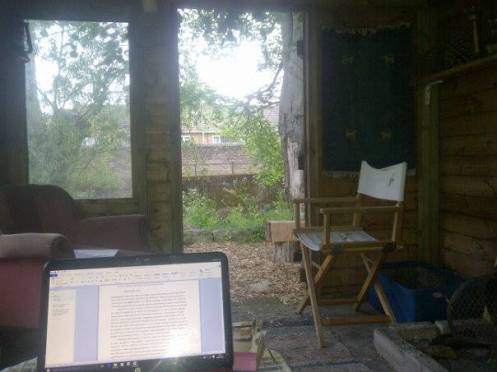

One older friend, a poet and academic who once had been my undergraduate tutor, asked if I would look after his house and cat for a series of weekends while he was away, which I did. With that experience of being in a different space for a clearly set time, routines became more possible – and that was key to how I properly got focused on the book. It was simply a matter of knowing: ‘I’m here for forty-eight hours, and all I’m going to do is write.’ I was thirty miles away from all the usual distractions and in this very atmospheric, sunlit old house with a long garden and a wood cabin at the end, beside the river Skell in North Yorkshire.

In spending weekends in that wood cabin I began to feel calm again. It was what gave me the template for a new routine I could enjoy and which I could – crucially – look forward to. I’m fortunate to have that experience, and I’ve since looked after the house and cat and cabin every summer. Most of the book was written there, as were many poems. It’s also a real delight to have friends come over to the house and cabin in some of the evenings.

I’m glad to say that I’m now much more contented in the space (another attic) where I live, in a shared house with two really good friends. But it did take a long time (and many repositionings of furniture in relation to light and shade) to reach this point.

During university semesters, I tend to get my writing done very, very early in the morning, usually starting at two. I can work that if I go to bed by about eight in the evening. It gives me about five hours of writing time before walking into work, though I can’t usually do the nightwork more than three mornings a week before tiredness catches up, and I start to turn off my alarm in my sleep.

SARA: You yourself are Autistic. How important do you think it is for Autistic people like you and me to be heard and seen, both by allistics and our fellow Autistics?

JAMES: Across psychiatry, society and culture, autistic people have had their critical perspectives and even just their voices ignored for way too long. Even now, although progress is visible, it’s still mostly neurotypicals (or allistics) who exercise almost all the power over whether, when and where autistic people are given a public voice.

Although Naming Adult Autism is frequently an angry book in critiquing the mainstream coverage of autism, the parts within each chapter move increasingly towards more progressive or often more radical texts. There are sequences on work by autistic poets (Les Murray and Joanne Limburg), on novels by Douglas Coupland (who in published interviews identifies as having Asperger Syndrome), as well as on some really valuable novels by authors who, so far as I’m aware, do not identify as autistic (Clare Morrall, Meg Wolitzer).

The most provocative novel dealt with was Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake. I’ve huge respect for Atwood as a writer, so those pages were hard to write. Seeing autism conflated with a pathological opposition to the arts and to fiction itself in a major literary novel was grim – though it did help to galvanize some of the book’s main standpoints.

I wanted to write about some less obvious texts in relation to autism, such as E. M. Forster’s novel Howards End, The Who’s 1969 album Tommy, Ricky Gervais’s The Office, and the Michael Andrews/Gary Jules song ‘Mad World’.

A most important thing, though, was to connect with and reflect on critical writings on autism by #ActuallyAutistic authors, such as Jim Sinclair, Damian Milton, Laurence Arnold, Sonya Freeman Loftis, Dinah Murray, Wen Lawson and Gillian Quinn Loomes.

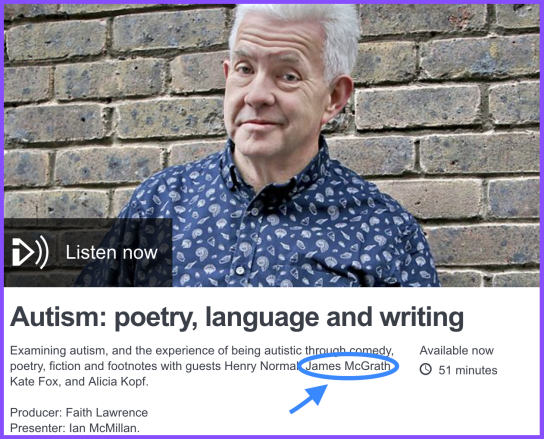

But despite the rapidly expanding wealth of art and scholarship from autistic people, how often are any of us are given space for expression in the wider media? It does sometimes happen, and I was delighted this spring to be interviewed for BBC Radio 3’s poetry programme The Verb with the poet and academic Kate Fox. Thanks to a genuinely forward-thinking producer in Faith Lawrence, Kate and I were given a space to properly challenge some of the misconceptions around adult autism. But such opportunities are rare.

It’s as if the media prefers autistic adults to reinforce existing stereotypes, and that’s something I challenge at length in the book. Autistic adults who question (or even mention) the status quo of, say, Simon Baron-Cohen’s models of autism are actually seldom quoted in the media. Similarly, academic research on autism by actually autistic scholars – despite being peer-reviewed and published – is far too rarely cited in psychiatric publications by non-autistics.

So yes, it’s vital for autistic individuals to be given greater media access: as a human, social right (of course) but also in order to redress the ways in which we have been, and still are, publically misrepresented.

Cultural misrepresentation leads only to further difficulties for autistic people. That’s a main concern of the book. We are expected to be good at science, IT, or nothing. Professionals who influence our lives, and who influence the possibilities of an autism assessment, sometimes fall for these misrepresentations themselves. So I’d love it if some professionals could read the book.

SARA: You note that the “Adult Autism-Spectrum Quotient Test” is skewed (For example, Autistics are not supposed to “get” fiction, according to that test). Can you talk about that a bit?

JAMES: The Adult Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) questionnaire is the most widely-disseminated screening tool for adult autism. It consists of 50 statements, with which we’re asked to agree or disagree. The AQ test was launched in 2001 by the University of Cambridge Autism Research Centre (UCARC) after being piloted in the late 1990s.

The test’s principal author was Professor Simon Baron-Cohen: one of the world’s most influential but also most divisive autism researchers.

Anyone with passing interest in adult autism is likely to have seen Baron-Cohen’s questionnaire. It’s widely accessible online and is reproduced in many books, journals, newspapers and magazines. It’s worrying to consider that some people’s knowledge about adult autism probably stems only from reading that questionnaire.

Now, I must emphasise (as Baron-Cohen does) that a high score on this test alone does not warrant actual autism diagnosis.

Crucially though, the test can be used by general practitioners – the gatekeepers of formal autism assessment for many people – in deciding whether or not to refer a patient on to an autism specialist. UCARC’s 2005 report on questionnaire’s validity concluded by advocating its value to general practitioners.

But what is less well-known is that in addition to being designed for a practical purpose within widespread medical procedures, the 2001 test was constructed according to a distinct research agenda. It is towards that agenda that certain statements on the questionnaire – and the scoring of their answers – are skewed. Scientifically unsound.

In the book, I go into very, very close detail on several problems with the questionnaire’s design and uses. But here, I’ll try and keep it brief:

- Professor Baron-Cohen designed the test along with Dr Sally Wheelwright at UCARC. Preliminary tests of the questionnaire’s validity were conducted by the two authors, plus three undergraduates named as co-authors.

- But as well as being created to ‘measure’ an adult’s autism ‘quotient’ numerically, the other purpose was to test, if not prove, Baron-Cohen’s headline-friendly theory (launched 1997) that scientists and mathematicians show more autistic traits than the general population.

- The questionnaire is strewn with statements relating to aptitude for STEM subjects: science, technology, engineering, mathematics.

- Each of the questionnaire’s answers that could suggest interest in numeracy are scored positively (raising the respondent’s autism quotient ‘score’). But each statement indicating engagement with the arts (especially reading fiction) is scored neutrally or negatively.

- So, the AQ defines numeracy as an autistic trait in its own right. Interest in the arts, conversely, is assumed to be the exclusive province of neurotypicals!! Yet, a possible result is that some mathematicians may have higher AQ scores because they are mathematicians – but not necessarily because they are ‘more’ autistic.

- Meanwhile, an autistic person who happens to enjoy fiction but not mathematics will come out with a lower autism quotient. And there are potential ramifications of these results.

- In 2001, Baron-Cohen et al reported on the trials of the test: ‘Scientists (including mathematicians) scored significantly higher than both humanities and social sciences students, confirming an earlier study that autistic conditions are associated with scientific skills. Within the sciences, mathematicians scored the highest.’ (Baron-Cohen et al, 2001, p.5)

Yet that just means that mathematicians score higher in a questionnaire that includes statements relating to numerical thinking. The earlier study apparently ‘confirmed’ here was a 1998 ‘Research in Brief’ publication led by Baron-Cohen and based on Cambridge University students, but that study itself was quite sketchy, as explained in the book.

In a 2012, in a TED talk proclaiming that autism may be linked to ‘minds wired for science’, Baron-Cohen implied that this idea was supported by the 1944 research of Hans Asperger. ‘He wrote’, states Baron-Cohen, that ‘for success in science, a dash of autism is essential’. In fact, Asperger said something significantly different. In 1977 – reporting on the adult lives of his former child patients – Asperger asserted: ‘it seems that for success in science or art a dash of autism is essential’ (emphasis added).

Asperger (1944) remarked on the flair some autistic children show towards maths and science, but in the same paper, described how others showed distinguished abilities in relating imaginatively to paintings and stories. One of Asperger’s most detailed profiles of an autistic person (ignored entirely by Baron-Cohen) describes a boy named Harro.

I wrote about Harro in the book. I think Asperger’s summary of Harro’s reading skills deserves the attention of anyone who believes that to be autistic is to be somehow indifferent to reading fiction:

‘one could notice clearly that he read for meaning and that the content of the story interested him … his reading comprehension was excellent. . . . he could say what the moral of a story was even though the moral was not explicitly presented’ (original emphasis).

As demonstrated from novels by Margaret Atwood to a sitcom such as Big Bang Theory – plus countless broadsheet articles citing Baron-Cohen – the association of autism with STEM has become not just a stereotype, but an expectation placed on many autistic people. Autistic scholars in the arts, humanities and social sciences may be a minority – it’s too early to say – but we are nonetheless here.

SARA: I absolutely love fiction; Fantasy and SciFi are my favorite genres! What are some of your favorite fiction titles and genres?

JAMES: I can’t imagine life without fiction. I’ve said it before, but for me, reading novels is a way into the world – a way of learning about people (including myself, when I identify with fictional characters). Reading a novel is far easier for me than watching a film. Unlike with films or TV, we can read at our own natural pace, and that for me makes all the difference.

Fiction has been deeply important to me since the age of hearing stories before I could read. One of the first stories I remember being delighted by was Ursula Moray Williams’ Gobbolino the Witch’s Cat. My sister and I had a tape of it, read by Sheila Hancock.

The novels I wrote about in the book were obviously there because autism itself occupies something like a ‘genre’ in fiction. Even so, in making notes on every page and just immersing myself in the reading, I absolutely fell in love with those novels – especially Clare Morrall’s The Language of Others and Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings.

I don’t tend to seek novels by genres, so much as themes – and houses are major themes in many of my favourite books. I wish it was recognised more often in society, culture and medicine, this thing of how almost unfathomably hard it can be for an autistic person to have to leave what has become their own home. In the book, there’s a footnote called ‘World is Sudden’ (a paraphrase of Louis MacNeice) where I try and address it, but there’s much more to say.

One of the most memorable things I’ve read on this subject is from the children’s writer Philippa Pearce, author of one of my favourite books, Tom’s Midnight Garden (from 1958). Philippa Pearce was not, to my knowledge, autistic, but what she said really speaks to me.

In an interview she did with a publishing magazine, which I read in summer 2000, working in a bookshop, Philippa Pearce described how she felt when the mill house in which she had lived as a child was sold. She said something to the effect of: ‘I had what could be called a nervous breakdown.’

Many of my favourite writers deal with ideas and experiences of home and houses. As a child, the ‘Green Knowe’ series by Lucy M. Boston (based on her own house) really enchanted me. The Green Knowe stories involve magic and ghosts, but it was really the sense of the house as a place and time that I read them for.

Also on themes and genres, my PhD thesis (completed some years before my formal autism diagnosis) was called ‘Ideas of Belonging in the Work of John Lennon and Paul McCartney’. Again, I focused closely on themes of ‘home’ – usually as something that has been left or lost. I also researched and wrote a lot from a social history perspective about the two main houses in Liverpool where Lennon and McCartney grew up. An important philosophical book for me at the time was Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space.

In research and writing at length about autism science in the book, being able to quote from literary authors – mostly poets – was like an intake of oxygen. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Oscar Wilde, Aldous Huxley and most of all William Blake were vital to me there. But the most empowering literary and philosophical influence was Simone de Beauvoir’s chapter ‘The Data of Biology’, at the start of The Second Sex. (Before beginning writing this book, I published a playful poem imagining a conversation between Beauvoir and Baron-Cohen called ‘Ventriloquy Soliloquy’, written on my first Christmas day alone in Leeds).

SARA: Chapter 3 of Naming Adult Autism considers the obstacles created recognizing Autistic girls and women. Can you please talk about some of these obstacles?

JAMES: One reason why I’m so glad you’ve asked me to do this interview Sara is because (like many people, clearly) I really admire – and have learned from – your blogging on this topic.

Another author on this who I highly recommend is Lesley Bonneville. A novel I read recently that deals with autism and gender brilliantly is Ta-Ra, Alice: Odyssey on a Shrinking Raft by A. Robertson. Ta-Ra Alice was published too late for me to write about, but I’ve posted a 5-star review of it on Amazon.

And, as discussed in Chapter 2 of the book, there’s Joanne Limburg’s The Autistic Alice. More recently, Laura James’s Odd Girl Out: An Autistic Woman in a Neurotypical World. A real highlight of the last few years for me was sharing a platform with Joanne and Laura at the Norfolk and Norwich Literature Festival.

Chapter 3 of Naming Adult Autism is called ‘The New Classic Autism’. Obviously, for something to be both ‘new’ and ‘classic’ is oxymoronic, and I use the term ‘new classic autism’ to underline both the superficiality and, I hope, the transience of a dominant pattern in early 21st-century autism narratives.

Basically, Chapter 3 confronts (and sometimes rages at) how certain wider power structures are shaping both cultural and scientific notions of autism. In most – and certainly the most lucrative – ‘portrayals’ of adult autism, science and culture present us with a white, professional-class, able-bodied male.

In terms of autism and gender, one of the most dubious but still influential models is Baron-Cohen’s much-publicized theory of the ‘extreme male brain’.

There numerous scientific inadequacies to Baron-Cohen’s extreme male brain theory. It’s important to unpack these because, although it’s great that Baron-Cohen and the UCARC are now at last placing more focus on women and autism, the ‘extreme male brain’ idea remains an all-too-familiar cultural and even medical reference point.

UCARC’s equation of autism with ‘maleness’ leans very heavily on the idea that autism is fundamentally characterized by lack of empathy. And according to Baron-Cohen, empathy is a female trait while systemizing is a male trait. That’s the crux of how the theory of autism as the ‘extreme male brain’ begins. The assumption being: autistic people lack empathy, and empathy – according to Baron-Cohen – is a female trait. Hence, the extreme male brain terminology. But for now, ‘extreme male brain’ is not a theory: it’s a metaphor. And metaphors, as discussed elsewhere, tend to be what we use when actually there is no clear or affirmative answer.

Baron-Cohen is a key researcher in the Cambridge-based Fetal Steroid Hormones project, publications on which announce links with prenatal testosterone levels and ‘autistic traits’. But actually, none of the people in the research sample were themselves autistic. The autistic ‘traits’ reported in those articles (reviewed in the book) are therefore tenuous.

It’s also noticeable that UCARC’s publications on autism, fetal hormones and biological sex are – like the earlier studies they cite – oddly less interested in the ‘female’ half of the human brain. The research is both quantitatively and qualitatively imbalanced.

SARA: You make a big push for “[…] promoting deeper, greater dialogue between the humanities and the sciences regarding the meanings of autism.” What are some ways we can foster and encourage discourse, mutual respect, and cooperation between the two regarding Autism and Autistic people?

JAMES: It sounds an ambitious aim, I know. But historically, the division between the study of ‘the sciences’ and ‘the arts’ is actually quite recent. I think the obstacles towards such greater dialogue are not intellectual, but merely practical. But they can certainly be overcome. Things like conference panels that welcome research both from the sciences and from the humanities (and social sciences) on autism are very slowly starting to happen, but they need to be much more frequent – and more accessible to the autistic population.

And also, simpler still – just reading work on autism from other disciplines. So I think this further dialogue is most definitely achievable – provided we’re all willing to take a few risks in reassessing our own disciplinary vantage points. And what’s the point in being an academic, if it isn’t to keep on questioning our own ideas in search of new knowledge?

Thank you for bringing this book to my attention. Have just downloaded it. Can’t wait to read it and add to my Book Review section of my blog.

LikeLiked by 2 people